The idea of considering elements of the environment (rivers, lakes, mountains) as ‘legal persons’ has been recently used as a juridical tool in various cases around the world. A similar movement concerning animals has been initiated by philosophers, lawyers and activists who question the boundary between humans and animals – especially those with superior cognitive abilities – and call for a change in the status of animals from ‘things’, that can be owned, to ‘legal persons’. Preliminary research reveals that the process of attributing legal personhood to nature differs from country to country and sometimes does not have the legal implications that it may appear to have at first glance.

For instance, the Non-Human Rights Project’s request to grant habeas corpus (bodily liberty) to one of his ‘clients’ – the elephant Happy – on the grounds that she passed the mirror test has been repeatedly rejected by U.S. courts, in part on the grounds that animals are not legal persons. In India, on the other hand, a High Court judge declared the entire animal kingdom ‘legal person’ without even clarifying which animals the ruling refers to. Cases therefore need to be studied not only by considering the legal reasoning but by taking into account the specific cultural and juridical context, in order to grasp what the legal categories used in the case exactly mean and what their repercussions are at a juridical and practical level.

Vincent Chapaux focuses on how the notion of habeas corpus has been followed in numerous cases where legal personhood has been requested for animals and for their ‘liberation’ : the case of the chimpanzees Suica (Brazil 2005), Kiko, Tommy, Hercules and Leo (USA 2013), the orangutan Sandra (Argentina 2014), the chimpanzee Cecilia (Argentina 2016), and the spectacled bear Chucho (Colombia 2017). In these cases litigations have a strategic character, with the ultimate aim of contributing to the liberation of all animals beyond particular individuals, of accumulating legal precedents and of establishing fundamental rights for animals.

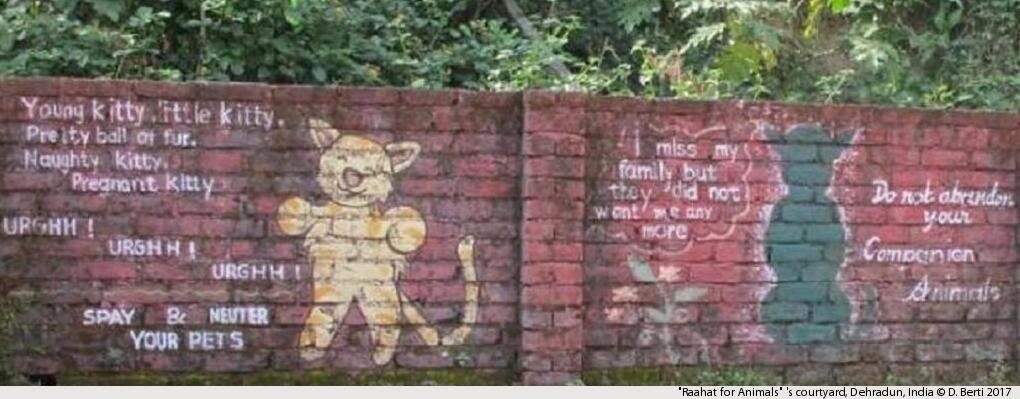

Daniela Berti analyses how the idea of ‘legal personhood’ has been used in India by FIAPO, an animal rights organisation whose leaders have been directly inspired by the Nonhuman Rights Project set up in the United States by Steven Wise. She compares the arguments and strategies used by these two organizations to defend their cases in court. Daniela also examines how the issue of granting legal personality to rivers and animals has been handled by judges in recent rulings and how such rulings may be perceived differently in India and abroad.

In Colombia, Sandrine Revet, Pierre Brunet and Carolina Angel Botero, examine the case of the Atrato River, which was granted legal personhood in 2017 by the Colombian Constitutional Court. Sentence T- 622 decided on the ‘acción de tutela’ – legal action for the defence of fundamental rights – taken by the environmental activists’ association Tierra Digna and various local organisations. Sentence T-622 implies several concrete measures (scientific studies on the contamination of the river and the inhabitants, military intervention for the ‘eradication of illegal gold mining’ and ‘reconstruction of cultural and ancestral traditions’). The novelty of this decision resides in the fact that it considers the river as a ‘system of relationships’, not merely as a resource for humans. The Sentence emphasises the interdependency between humans and ‘non-human’ elements in the river basin, in connection with the concept of ‘biocultural rights’. Claire Duboscq will undertake fieldwork in a region between Bogota, where she’ll meet the institutional actors in the jurisprudence studied, and several peripheral areas, where conflicts lead to the personification of rivers – these selected case studies will allow her to apprehend the multiplicity of local actors who contribute to the making of nature’s rights ».